A number of years ago in Madrid I had a conversation with a man who compared the lack of choices on European restaurant menus to a form of mind control. In the US, he suggested, where restaurant menus are more expansive, minds expand accordingly and people question other things.

It’s an interesting idea, though perhaps chicken and egg. But apart from mind control or mind expansion as a byproduct of menu size, do people actually make better ordering decisions when they have larger menus?

Research shows that on day-to-day issues an abundance of choices leads to lower purchase levels and even to less satisfaction with the selections made. So does that mean that “mind expanding” choices result in less buyer value? What about when buyers take the time to consider and weigh all of the options? Does more information lead to better decisions?

I often deal with large-scale corporate decision-making by advising clients on investment decisions: for example, where to build a new facility or what vendors to select.

One issue with projects of this sort is that large decisions are often generational events in which the client invests perhaps hundreds of millions of dollars in the outcome. Because these events are relatively rare, it is impossible to take a portfolio view by making many comparable smaller decisions and studying which worked well in what situation.

Instead, when there is a single large decision to be made, it often becomes a question of understanding the drivers of value to the organization, conducting due diligence on each option and considering the qualitative issues involved in each choice. Where final options were similarly good, I have seen decisions swayed by anything from the driving distance of management to the proposed new facility location to whatever option was more similar to stories currently in the news. At that point, a good consultant’s talent is to accommodate the whole organization’s needs while also giving some allowance for those that will have to live with the decision.

Sunday, March 30, 2008

Choices, choices

Labels: business

Thursday, March 27, 2008

Cultural insight

I met Cathy Bao Bean recently at a Claremont Graduate University alumni event (I’m not an alumnus, but was there as a member of the Peter Drucker Society). Cathy is the author of a great book called “The Chopsticks-Fork Principle: A Memoir and Manual” as well as being a really enthusiastic and interesting conversationalist.

I read her book the day after I met her. Many of her cross-cultural stories reminded me of what I experienced while working in China over five years. Much of the business I did then (and even now) involved understanding the meaning behind peoples’ words (or lack of words) and cultural differences. I wish the book had been available before I went to China in the mid-90s, since it would have helped me understand some things more easily.

Labels: culture

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

What small business teams can learn from jazz

- The better you listen, the better you play and the better the group sounds

- Everybody has a role

- Low hierarchy can work well

- Even solos take place within the context of the group

- By following a few simple rules, you can make great things happen

Labels: business, creativity

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

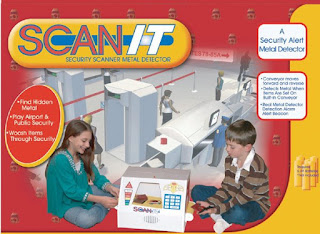

Toys of the times

I was amazed when I heard about this toy. Rather than using a toy metal detector to search for buried treasure, it's a way to educate kids about airport security. Now we just need knowledge worker toys for kids. There could be a toy kit for being a management consultant, investment banker, marketer... maybe not.

From their website: "This unique toy/teaching aid provides ample amounts of healthy fun along with education and awareness of the security measures that people face in real life."

http://lifesinventions.com/index.cfm?fuseaction=product.display&Product_ID=2385&CFID=17420493&CFTOKEN=53095688

Labels: culture

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

On training impact

I often see clients with corporate training plans that seemed based on the premise that employees have a right to training, just not the right to use what they learn. Most training courses follow a one-time course model that has no follow-up. In a typical training course that might last a couple of days, employees can be exposed to new ideas and methods, but hardly have the opportunity to practice what they have learned. Under these conditions, how much new knowledge do they retain?

Even more problematic are training courses delivered right in the employee’s office via distance learning. While many companies prefer these courses because they are less expensive, their design means that employees are more easily distracted and tempted and expected to check in on their regular work that they are missing.

One company that seems to have got training – at least company-wide training – right is GE. For example, GE’s Six Sigma program has employees attend four weeks of training in statistics, processes and quality control and then requires employees to use what they have learned while working on or leading Six Sigma projects. Top management, many of themselves former Six Sigma “Black Belts”, supports the training.

I’m not making a case for implementing Six Sigma, but the integrated approach that GE takes seems to lead to more learning and higher payoff.

While it may not be practical to do the same with shorter, more specific courses that only apply to a small number of employees, companies can do a few simple things to increase their return on training investment.

- enforce a minimum amount of training per employee annually (dollar amount, credit amount, or time amount)

- encourage employees to take training outside of the office

- After an employee receives training, require them to deliver an internal training session to others. The purposes of these sessions should be to both transmit knowledge elsewhere in the organization and to make sure that the new training sinks in over time

Labels: business, organizational behavior, productivity

Sunday, March 9, 2008

Permanent space vs. hoteling

Some businesses have done away with permanent office space or cubicles. Instead, when an employee is in the office he or she registers for a place to sit and depending on availability gets a spot. Work or personal items that would have been kept in a permanent desk drawer may now be kept in a locker and moved to the temporary space each day. Colleagues who wish to find others may look them up on a website directory which lists the identification number of the cubicle or office which they are using that day.

The entire argument for hoteling, as this is known, is financial. Reduce your office real estate and save on the bottom line. However, what is lost from the top line in this structure? What is lost in terms of worker productivity and morale?

Labels: business, productivity

Friday, March 7, 2008

Rules of lunch, or Why to take a break

A few years ago I had a client who was a senior member of a large real estate development firm. During one lunchtime conversation he looked back over a career that spanned 40 years and talked about a few of the things he had accomplished of which he was proud. One of them, curiously, was his “lunch policy”. He has lunch almost every day in the office with colleagues of all levels. At lunch he has two rules. First, if you are busy with something or have other plans you take care of lunch yourself and don’t disrupt the lunch of others. Second, at the lunch table no discussion of work is allowed.

In the past, when I worked at a traditional management consulting firm I found that to many colleagues, lunch was just a time of day when you happened to eat while working. The idea of leaving the office to eat somewhere else while not working was foreign and the perception of having done so was to be avoided. I could never understand why people could think that being seen working through lunch would make them more effective or raise their perceived value to the firm. Eventually I came to eat lunch with the colleagues who felt the same way I did or with clients who never even heard of the issue.

I never could figure out what kept the others so busy. In fact, I came to believe that they were always working because they were less efficient due to the fact that they were, you guessed it, always working.

My recommendation is to take a break, go out, walk around, refresh your mind and be more productive.

Labels: business, creativity, organizational behavior, productivity

Tuesday, March 4, 2008

Does social networking keep people from changing and developing?

When I grew up I didn’t know anyone who used email, cell phones were rare, and social networking websites were non-existent. As a result I had no simple way to stay in touch with most people I grew up with, especially when people moved. In the past I also knew a great number of people whose phone number or address I never learned, but whom I would see regularly. Staying in touch didn’t seem to be a problem.

Contrast that with a younger generation that will probably maintain some contact with most of their friends from high school throughout their college and working years. Even if the contact is passive via a social networking site, one potentially may maintain that network forever rather than losing it with physical distance.

On the rare occasions when I meet up with friends from more than a decade ago, the retelling of stories of the past and common memories means that we often temporarily settle back into the personas and styles of those earlier years. However, these situations are the exception for me since I only occasionally see my friends from youth as is probably typical of most people my age who have moved around.

Would one be less able to change if that cohort of friends followed one through life via today’s social networking tools? If so, will the generation that grew up with Friendster, Myspace and Facebook change less over time from its youth? Will the unbreakable threads of history keep this generation from evolving?

Labels: culture